Curated by Dalya Islam

This entirely new body of elegant and thought provoking work preserves the major themes that charmed and engaged me in Emanuele’s practice when I first came across it, but also departs along interesting new avenues of thought and expression.

The title of the exhibition Quod Vides, Totum is drawn from the writings of the major stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger, 4 BC-64 AD. Born in Granada in modern-day Spain and later practicing in the Roman Empire’s capital city, Seneca’s discussions of nature hold a particular fascination for the artist.

In his multi-volume work on meteorology Natural Questions, the philosopher proposes that the study of nature is ultimately the study of humanity. He posits that in observing the world around us, in knowing that all this (literally: quod vides totum) pertains to him, man is obliged to study his environment. For in studying nature man frees himself from the bonds of every-day concerns, and liberates himself from the triviality of power and material possessions. It brings man to an awareness of his essence, his place in the cosmos and the natural order of things. It brings him peace and eventually leads to knowledge of God, or as Seneca says “at least, to the beginnings of such an understanding.” (NQ 1.13).

Emanuele’s modus operandi is the physical enactment of this study, the study of man through nature. Devoting days to woods and wild landscapes the artist captures the trees, the sunlight, the leaves, shadows and running water in an effort to deliver both beautiful pictures and subtle metaphors. These exquisite photographs are cogent reminders to look beyond the immediate world we inhabit, to expand our vision, to “see the view from above,” an influential phrase coined by the philosopher Pierre Hadot describing the view that liberates us. Seneca’s philosophical discourse is a fundamental theme running throughout Emanuele’s practice and consciously drives her choice of subject matter.

“Only when we view our lives from the perspective of the stars do we come to see the insignificance of riches, borders, and so on” (NQ 1.9–13)

Seneca believes that in order to find true equilibrium man must also study his environment to note the passage of time, and uses as an example the cyclical aspect of natural phenomena such as day and night and ocean tides. For in becoming conscious of this quality in our universe, and thus in the nature of our own existence, we not only abolish a preoccupation with inconsequential matters but ultimately practice living in the present.

In essence all the images in this exhibition are reminders of the passing of time, they are fleeting moments captured in perpetuity by the artist’s camera, the light will change, the leaves will fall and even in the same day these subjects will metamorphose into something else.

“To use the present well is to be aware of completeness. More days, and months, and years, will make up our lives. But we should not think of them as stretching out into the future; rather, they are concentric circles surrounding the day which, right now, is present.” Vogt, Katja, "Seneca", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

As we touched on earlier Seneca proposes that the natural world is a sign of God’s existence. The Natural Questions are composed of long descriptive tracts on clouds, trees, lightning, thunder, earthquakes and in particular the River Nile. The Nile is a perfect microcosm of the cycles of the earth, flooding yearly and silting the earth: a force for both destruction and creation. By removing the mystery of meteorological phenomena through physical analysis Seneca attempts to prove to his contemporaries that these are not the whims of Zeus but signs of a single monotheistic God. There is a fascinating alignment in these Stoic ideas with the teachings of the Qur’an in which Signs are given as evidence for Allah’s existence:

“And in the earth … are gardens of vines and fields sown with corn, and palm trees - growing out of single roots or otherwise; watered with the same water, yet some of them We make more excellent than others to eat. Behold, verily in these things are signs for those who understand.” The Qur’an, Sura 13, v.4

Modern commentators also propose that these long passages with such grandiose turns of phrase are more than just an attempt to extract the mystery from meteorological phenomena, but are also an artistic engagement with nature that “contrasts the beauty of nature’s workings with the ugliness of vicious action.” In his book The Cosmic Viewpoint: A Study of Seneca's Natural Questions, G Williams proposes that the construction of these passages is, in itself, an oblique reference to a Stoic behavioral model that holds up nature’s beauty as moral guidance for good and just behavior.

Emanuele’s images are more than just beautiful examples of the woods and the sky, they are vital reminders of philosophical thought. These visions of nature address fundamental concerns such as our place in the world, the passage of time, Stoic behavioral practice and the existence of a higher power. Ultimately they embody all these concepts in an effort to promote awareness, self-study and most importantly a sense of contentment.

* * *

The title of each work of art is conceived in Latin. Emanuele pays tribute to the ancient philosopher who so inspired her by employing the lingua franca of his era. It is also a conscious mimicry of the botanical names of plants. Here though the names are transformed from dry, scientific titles into Latin translations of the emotions and concepts the subject evokes in the artist, Animae Necessitas for instance literally translates as ‘a yearning in my soul’.

Clearly Emanuele has a deep reverence for nature, the earth, the sun, the wind and the rain. She honours these natural wonders through various photographic techniques including intense close-up [macrophotography], effectively bringing the viewer into immediate contact with the living essence of the earth. In Animae Necessitas a halo of sunlight shines through rippling grass, and in Architectura Glaciei crystalline water droplets freeze onto winter foliage. The lushness of the former and the cool crispness of the latter transport the viewer to a place of meditative calm, intentionally fostering an awareness of both place and self according to Seneca’s teachings.

In Sola Adeo the artist exhibits a skillful handling of the camera and an eye for detail in the clever manipulation of optical illusion. By rendering the trees in the foreground with neither tops nor roots Emanuele gives a sense of expansion, of eternity in the repetition. There is latent power in this image, a sense of stillness and anticipation. Much like the manner in which the stylized tulips of Ottoman Iznik tiles are replicated, alluding to the heavenly gardens, here nature becomes a sign of something far greater and more imposing; another subtle reference to Stoic doctrine.

The idea of the passage of time is elucidated in Circa Adolesco where Emanuele’s lens captures the swirling limbs of a plant physically echoing the cyclical character of the universe according to Seneca. The artist composes the image using Italian Renaissance principles of recession, by leading the eye to the top right corner of the image Emanuele exploits a classic technique for creating an illusion of depth. The image of the path itself is potent and heavy with symbolism: the lonely road, the hidden path, the Straight Path, the Path of Righteousness. There is concept, skill and beauty in Circa Adolesco, an image that is both an allegory of order and chaos and an exhortation for conscious thought.

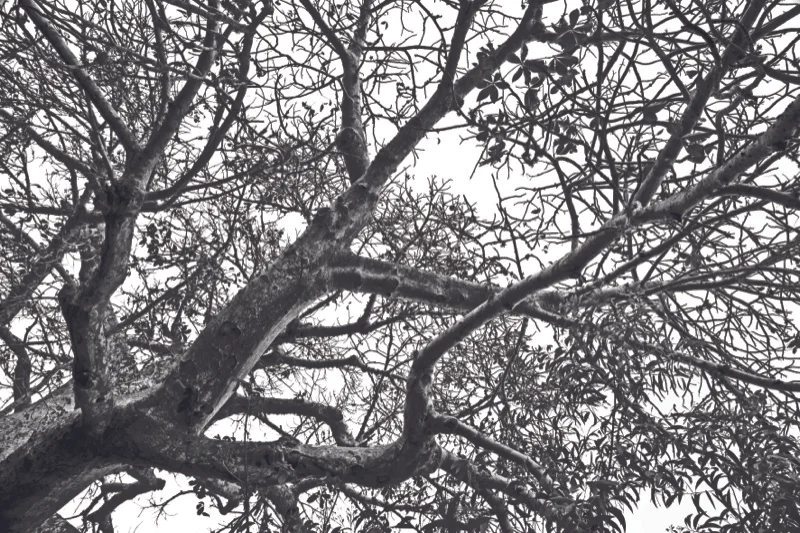

In other works such as Ab Humo Emano and Orbis Astri the artist plays again with perspective. Here Emanuele turns the camera to the firmament, tracing the tree trunks to their tops and eliciting that breathless sense of wonder that comes from gazing upwards in a wooded place; a compelling reminder of the inconsequentiality of material wealth and possessions in the greater scheme of things.

Emanuele introduces human influence in Me Subicio Imperio. Cargo ships sitting low in the water are lost in the glitter of the sun on the sea, trees loom in the foreground eclipsing these marine monsters with their benevolent forms. The influence of man in Emanuele’s utopian vision is in direct contrast to the retardaire Victorian domination of industry that is in general still prevalent today. The sense of nature as more significant than anything else is evident throughout Emanuele’s practice, nowhere more so than in Me Subicio Imperio and the sister work Avius Advena.

This idea of the triumph of nature is also referenced in Solis Sollertia. The ancient twisted form of this grand old arbor is shot from below highlighting the magnitude of the tree, its mass and its quiet power in this beautiful deserted place. The combination of the noble subject and an adroit use of technology produces a potent image of nature enthroned.

In other images Emanuele plays with the shadows cast on the walls of crumbling ruins, further driving home the concept of nature’s dominion. In Oblitus Est and Ab Urbe Condita strong sunlight casts deep shadows on the exposed bricks and stone, the imprint of nature’s essence is conveyed without question. It is the stamp of the supreme on something transient.

More than that though, and true to her Classical roots, in these particular images there is a clear reference to Plato’s Analogy of the Cave, an analogy for hidden knowledge and hidden truth. Imagine a group of people chained to a wall, watching shadows projected onto the wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them. It is the hazy shadows they see, not the truth. This, said Plato, is the closest that the prisoners will ever be to viewing reality. It is a reference to the true form of existence and awareness and higher knowledge, it is a message that the material world is known to us only through sensation and that we possess the ability to perceive a higher and far more fundamental kind of truth if we can only remove the obstacles. To see the tree and the sun behind it, not just the shadow on the wall.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this new body of work, other than the signature shadow-boxes Mater Familias and Lemures Saltates, where the artist experiments further with her unique installations of light, wind and shadow, is the special commission of a video work by the BMG Foundation for the exhibition in Jeddah.

The video piece Aqua In Obscuritate combines all aspects of Emanuele’s practice: her Utopian vision, her reverence for nature, its beauty and power and the philosophical ideals of antiquity, these elements all combine in enigmatic soundscapes and imagery. As per Seneca’s doctrine time and the importance of existing in the present is encapsulated beautifully in the sound and vision of water flowing, a symbol of the flowing passage of time. Acqua In Obsucritate is a natural progression for Emanuele and a truly innovative step for the artist.

“Water is also my muse, appearing sometimes as the main character, sometimes as a mirror, sometimes as rain, sometimes as tears. In all cases it comes to my lens in its purity and transparency.” The artist in conversation with Dalya Islam, December 2012.

QVOD VIDES, TOTVM was exhibited in Saudi Arabia in 2013 at the Italian Institute of Culture of Jeddah and at Alaan Artspace in Riyadh.