Curated by Luca Beatrice

Wikipedia, that immense receptacle of notions, defines the term Ekphrasis (derived from the Greek), as “a verbal description of a work of visual art”. In deciding to entitle her exhibition with this archaic and obsolete word (today of course, young artists prefer to utilize English, the language of globalization, rather than returning to their own classic matrix), Teresa Emanuele leaves it up to the critics as she confronts us with a series of photographic images of rare beauty, almost entirely in black and white - only a few have just a hint of color that remind me of old postcards from childhood. These snapshots need not tell us where, how or when taken, and represent her latest intuitions on nature and the relationship that today an artist has with it. Taking a different turn from the usual path, her work could almost be accused of excessive literariness; more and more frequently on display are photos of suburbs, public housing, destruction and it has become more rare that the indiscreet camera’s eye captures something particular that in itself gives beauty. The absolute theoretical originality of her work, presumably a limitation, is actually her strong point especially when compared to the widespread style of dull and careless photography that respects neither synthesis nor its implicit linguistic rules.

In searching for an exact idea of ekphrasis to better approach Teresa Emaneule’s work, a paragraph taken from Feticci (Fetishes, ed. by Il Mulino 2012) by essayist Massimo Fusillo comes to my aid with its study on the patterns between investments in objects of a certain symbolic value and fully accomplished creative fiction, in literature, film and visual arts. First of all, if a work is meant to emanate seductiveness, the way that it will be narrated is decisive, pausing for example on a detail within the margin rather than focusing on its true meaning. One can criticize by choosing a centripetal movement or a centrifugal one; I personally choose the latter. In fact Fusillo states, “the descriptive attention towards the world of objects has for a length of time been assigned to the margins”, being considered excessively verbose and digressive. And yet, he continues, “the interaction between words and images, time and space, narration and description goes back a long way, beginning from the ekphrasis of Achilles’ shield in the Iliad, where the visual is transfigured freely into a tale”. By extension, all those digressions and pauses from the principal theme belong to this literary figure; frequently in classic works (from Don Chisciotte to The Betrothed), the plot could have been resolved in just a few pages if the authors had not chosen to devise a delay mechanism, thus skillfully exercising an ekphfrasic function). Truthfully, even when “ekphrasis is focused on one static moment, suspending temporality, it never excludes tension in the narrative” and therefore “one can never make a clear distinction between description and narrative solely on the basis of the presumptive essence of single expressions”.

Gradually moving away from the classical to confront the modern age, some forms of literature reveal a propensity towards ekphrasis, for example authors such as “Diderot, Baudelaire, Ruskin, Proust, Woolf, and Rilke who avoided detailed analyticity, preferring creative and evocative criticism based on the idea of perception as infinite”. According to Fusillo, it is important to avoid that the concept of ekphrasis coincides with that of blunt art criticism and incidentally he cites a text from James Heffernan’s Museum of Words (2004) where he advises us that “ekphrasis is the verbal representation of a visual representation that should not be confused with pictorialism, the presence in literature of visual effects, nor with iconicity, the literary use of graphic techniques that bears a similarity to the content of the work”.

We are rapidly getting closer to the poetic sense of Teresa Emanuele, whose work is actually based on the practice of isolating something precise from the mechanism of story-telling, notwithstanding the fact that she enjoys organizing her photographs in series - “Ecfrasi al sole, Ecfrasi dell’acqua, Ecfrasi solitaria…” and so forth. Since the era of Bauhaus to this age in time, we indeed have developed a concept, perhaps excessively schematic; ornamentation is a crime (Adolf Loos) and in any case, “less is more” (Mies van der Rohe), a concept which in a certain sense is inherited from the conventions of the classic age and according to which, description is artificial. However, the pauses in the narration, the proliferation of digressions are actually what gives rise to fullness in a narrative - “the infinite pleasure of enchanting story-telling which coincidentally fascinated Goethe”. Particularly prevalent in literary critique, and also in art, is “the position of the Marxist writer Lukacs, who contrasts the realism of Balzac, where descriptive details are always functional in relation to tales and persons, to the Impressionism of Flaubert and Zola in which specific details become an independent still life without integrating into a uniform and organic context”. To this I would add Impressionist art, coincidentally considered the first outpost of the 20th century Avant-garde movement.

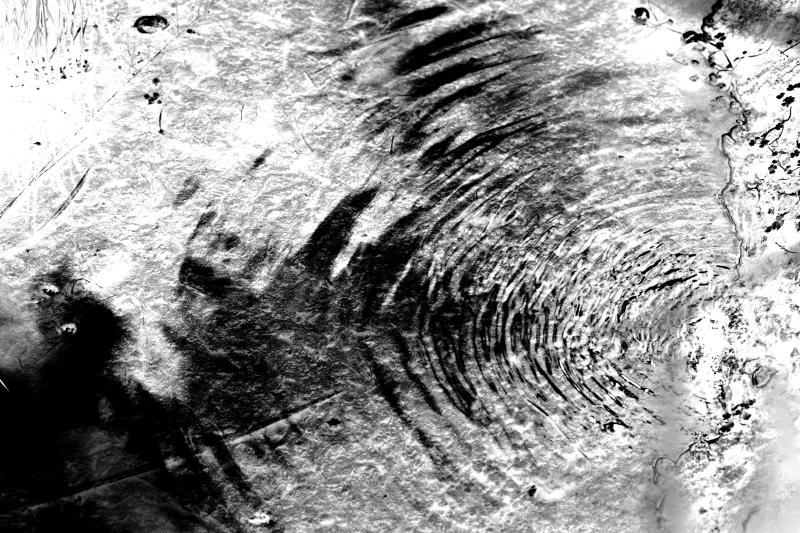

The artist is obsessed with trees that she regards as being “the only living things that continue to grow throughout their entire existence, always upwards, towards the light, towards the sun; I adore their static stance and their silent wisdom”. Observing the dewdrops on a leaf, the symmetric perfection in a small branch, a row of trees lined up like troops at ease causes us to reflect on those objects (that Fusillo refers to as fetish) intimately linked to anti-hierarchy, and “to the valorization of details, of the everyday, of material things where the description and entire dynamics of that which is visual continues to gain credibility, as did the modern romance novel after Flaubert”. We are speaking of insignificant objects of daily use and their primary function is to tell us, “…we are reality” (Roland Barthes).

The focal point of Teresa Emanuele’s camera pertains to the world of nature. We shouldn’t inconveniently use the adjective “naturalist” that was applied to painting in the mid-1900s ; after the crisis of the Informal movement, art was faced with the necessity of finding a more profound anchorage with reality without descending into the excesses of Realism. We could perhaps refer to traditional landscape photography in black and white with its wide spectrum that goes from Mario Giacomelli to the Iranian film director Abbas Kiarostami, from Ansel Adams to Olafur Eliasson (his works are merely interludes between one installation and another, but intense), however this is not exactly what we are dealing with. Teresa Emanuele is a contemporary artist, accustomed to her independence and to confronting the heated news of today (from a New Yorker’s cosmopolitan views to humanitarian work in Africa). She’s an artist and a nomad but by no means tempted by reportage; she’d rather question the cultural role of nature in the third millennium and how to best represent its critical state that lately has triggered an element typical of 19th century philosophy. According to Romanticist poets and painters, who borrowed suggestions from Kant’s Critique of Judgement, when confronted with the beauty of a particularly enchanting and evocative landscape, it was impossible not to seize the sinister and hostile aspect; a tall mountain, a night sky, or a rippling sea, must have upset the souls of Jacopo Ortis, the young Werther and the painter Caspar Friedrich. The Romanticists loved to involve themselves in emotional inner sentiments, but today nature threatens us because it is threatened by human irresponsibility and folly.

Teresa Emanuele is not bothered by this “environmentalist” aspect that inevitably makes us reflect more responsibly on the devastating effects to nature’s balance, nor does she evoke a sort of Lost Paradise, or a pastoral Eden. She simply chooses specifics and digression, shadows rather than light, in an attempt to give movement to the surface space already rich in vibrations. She also loves to talk about all of this with simplicity going directly to the heart of her emotions – “I am fascinated by the challenge of using a static means par excellence. I want to trap shadows while I write with light. A shadow is a mirror of what surrounds us but without an identity. My shadow is me, but without a face. The shadow of a tree traces the hours of the day with no distinction of season. I captured my tree; I got it. Twice. The first in that fraction of a second when it stood still for me. The second, today, in my box. I captured its identity and its faceless shadow”.

Translation from original text by Valencia Scott Colombo

ECFRASI was exhibited in 2012 in Venice at Contini Arte Contemporanea.